Urban ecology

Urbanization is a main trend, with already more than 50% of all people living in cities. For these city-dwellers, the nature in cities is the nature that they experience in their day-to-day life. While humans have been surrounded by nature during most of their evolutionary past, nature in cities has become less and less as cities grow and densify. Because nature in cities has a multitude of beneficial effects on humans, there are national and international calls to increase nature in cities, yet our planning procedures are not yet adapted to plan for and with nature.

In our work, we focus on two lines of research. First, we aim to understand why species can live in a particular place in the urban environment, focusing on animals. We use state-of-the art methodologies such as acoustic monitoring or insect identification using AI to find out who lives in the city and where, and link species occurrences to a detailed description of the urban environment. Second, we cooperate with colleagues from urban planning disciplines, from urban planners to landscape architects, architects and engineers, to develop planning and design methods as well as tools that will help to increase nature in cities. These two lines of research are presented below.

Understanding the occurrence of animals in cities

Early urban ecology studies have compared places outside the city with places in the city to identify what species can life in the city. These studies have found that in the city centre, where most of the surface is sealed, very few animal species can live (such as the Marienplatz in Munich), while in other places within the city, many species occur. A study carried out during the PhD-thesis of Fabio Sweet in our group found that across 30 cities in Germany, 80% of species found in a radius of 50km outside the city are also found within one of the cities1. However, many of these species only occur in a few places in the urban environment. In our research we aim to understand why a species occurs in one place of the city, but not in another. Understanding the conditions that allow species to live in the urban environment will help to design the city in a way that the species can live there.

We investigated biodiversity in 100 urban squares, to understand how human design affects the occurrence of animals in cities. We focus on public squares (open spaces in a city without housing that are publicly accessible) as a core element of cities that serve as important public spaces where city dwellers have gathered since ancient times. The 103 squares are a representative sample of all squares in Munich and span gradients in size, distance to the city centre, and greenness on and in the surrounding of the squares. We monitored the abundance and diversity of various animal groups to investigate the effects of square properties on urban biodiversity. We found positive effects of an increasing greenness (proportion of grassy surface area, number of trees, shrub volume) on the abundance and diversity of various taxa2. Importantly, we found that the most important variables also differed for different guilds within the same taxon, e.g. tree density on squares increased the abundance of tree- and ground-foraging birds, but had little effect on understorey-foraging birds3. Such birds benefit from the presence of shrubs. The greenness in a circle of 1km radius around the focal square increased pollinator abundance and small mammal activity, emphasising that several spatial scales can be important for biodiversity in an urban site. We are currently extending this study in the framework of Research Training Group in Urban Green Infrastructure, extending our study to more than 500 points in the city and studying not only birds, but also insects.

We also combine bird recordings with measurements of tree structure in the project CitySoundscape, aiming to further increase how urban structure affects the occurrence of species.

Another important limitation for animals in the city is ecological connectivity. In two PhD-theses we investigate how connectivity for animals can be measured and modelled in the city, and how such connectivity modelling can be included into urban planning. In the Ph.D.-thesis of Lisa Merkens, a new model for animal connectivity is developed and applied that uses new ways to integrate different types of species data for model parametrization. In the Ph.D.-thesis of Meret Pundsack, practical ways in which the ecological connectivity model can be integrated with models of other urban disciplines, such as traffic or microclimate planning, are sought, using multidisciplinary scenario creation and modelling (see CoCoNet-project).

Finally, we investigate human-animal interactions in “The Happy Pigeon Project”. Animals experience stressful lives needing to procure sufficient resources to survive and reproduce, while navigating predation threats and competition in the landscape. However, urbanisation introduces plenty of novel feeding opportunities for wildlife capable of exploiting them. Examples range from recreational bird feeding to food waste and litter. What happens then, when the pressure from food scarcity is relieved? Using urban feral pigeons as model organisms, the Happy Pigeon Project examines how food availability affects chronic stress in birds, using physiology (hormonal and morphological) and behaviour as wellbeing indicators. We conduct fieldwork in three German cities non-lethally managing pigeon populations via the Augsburg model, in which pigeons are provided food and nest sites (and their eggs destroyed to control breeding), thereby functioning as semi-natural food supplementary experiments. We also study captive feral populations, to understand how pigeons experience security - of resources, and from predators - when this comes at a cost of physical freedom.

==

1Sweet, F. S. T., B. Apfelbeck, M. Hanusch, C. Garland Monteagudo, and W. W. Weisser. 2022. Data from public and governmental databases show that a large proportion of the regional animal species pool occur in cities in Germany. Journal of Urban Ecology 8:juac002.

2Fairbairn, A. J., S. T. Meyer, M. Mühlbauer, K. Jung, B. Apfelbeck, K. Berthon, A. Frank, L. Guthmann, J. Jokisch, K. Kerler, N. Müller, C. Obster, M. Unterbichler, J. Webersberger, J. Matejka, P. Depner, and W. W. Weisser. 2024. Urban biodiversity is affected by human-designed features of public squares. Nature Cities 1:706-715.

3Mühlbauer, M., W. W. Weisser, B. Apfelbeck, N. Müller, and S. T. Meyer. 2025. Bird guilds need different features on city squares. Basic and Applied Ecology 83:23-35.

Development of methods and tools to increase biodiversity in cities

In the traditional self-conception of urban planning and urban design, as well as in the practice of the profession, biodiversity does not represent a goal-setting planning content, but rather a restriction that must be dealt with when necessary. This is the consequence of the genesis of modern urban planning, as the discipline had set out to rationally produce the modern city on the basis of scientific knowledge and technological progress4. It is thus necessary to bring designing for biodiversity actively into the different disciplines responsible for urban planning, such as architecture and landscape architecture.

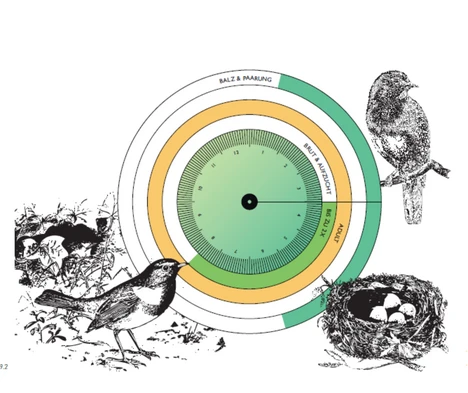

We have developed a methodology that we refer to as Animal-Aided Design®, which aims to overcome the rift between landscape architecture and conservation. The basic idea of Animal-Aided Design (in short, AAD) is to include the presence of animals in the planning process, such that they are an integral part of the design4. For AAD, the desired species are chosen at the beginning of a project. The requirements of the target species, i.e. their life-cycles, then set boundary conditions and serve as an inspiration for the design. More information on AAD can be found on the Animal-Aided Design webpage.

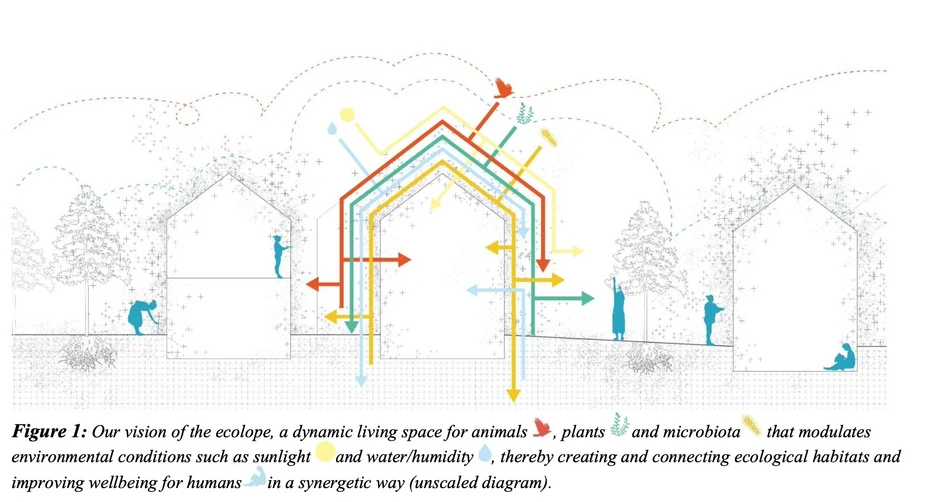

Making cities more biodiversity-friendly also requires to activate architecture for the support of biodiversity. This is because constructions cover large parts of the urban footprint and designing these is the domain of architecture. In the project ECOLOPES, an EU-funded FET-Open project (2021-2025) we investigated how architecture, computational design and ecology can be integrated to create ecologically sound buildings5. ECOLOPES proposes a radical change for city development: instead of minimizing the negative impact of urbanisation on nature, we aim at urbanisation to be planned and designed such that nature –including humans– can co-evolve within the city. We envisage a radically new integrated ecosystem approach to architecture that focuses equally on humans, plants, animals, and associated organisms such as microbiota. ECOLOPES has provided core approaches, models and technology that will help to achieve this vision. More information can be found on the ECOLOPES homepage.

One important component of making architecture biodiversity-friendly is to model the development of plants and animals living on or close to the building. In the Ph.D.-thesis of Laura Windorfer we investigate how architecture affects and can be optimized to provide high biodiversity (Protohab).

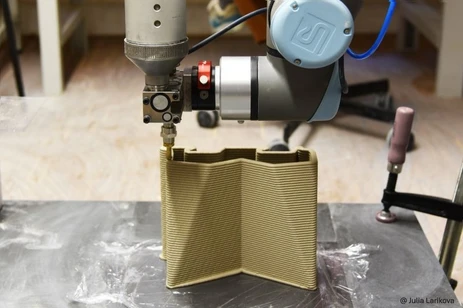

Design for biodiversity not only requires new planning and design strategies, but also new tools that can help to implement biodiversity-friendly measures. In a cooperation with Kathrin Dörfler, Professor for Digital Fabrication, designing for biodiversity and designing climate-active facades have been combined in the Ph.D.-thesis of Iuliia Larikova6. In the Nest façade customised ceramic elements were developed in a way that their complex geometry provides shelter and nesting opportunities for different animal species. At the same time, the geometries were digitally optimized for self-shading of the building envelope, which leads to a reduction of the façade’s surface temperature, particularly during summer. A prototype has been installed in Munich and it will be tested whether birds and mammals will use them.

Finally, biodiversity-friendly urban planning will only take place if city dweller want it. Interestingly, little is known about how people judge different types of animals and where people would like to see them. We investigated where people would like to see animals in the Ph.D.-thesis of Fabio Sweet. He found that there was a place for most of 30 animals that humans should place somewhere in the city, based on a questionnaire that was distributed in the city of Munich6. While people wanted animals to live in the city, they placed them away from their home, balcony or garden. Animals that they liked more were on averaged placed on locations closer to their home. The results show that city dwellers will accept conservation measures for animals in the city, but they are sensitive towards what species it is and how close the species come to their own private spaces. More detailed analyses showed that people that enjoy spending time in nature more, or help animals in their environment, generally accepted most animals closer to their home. In contrast, people who live in a house instead of an apartment generally wanted most animals further away from home7.

==

4Weisser, W. W., and T. E. Hauck. 2025. Animal-Aided Design–planning for biodiversity in the built environment by embedding a species’ life-cycle into landscape architectural and urban design processes. Landscape Research 50:146-167.

5Weisser, W. W., M. Hensel, S. Barath, V. Culshaw, Y. J. Grobman, T. E. Hauck, J. Joschinski, F. Ludwig, A. Mimet, K. Perini, E. Roccotiello, M. Schloter, A. Shwartz, D. S. Hensel, and V. Vogler. 2023. Creating ecologically sound buildings by integrating ecology, architecture and computational design. People and Nature 5:4-20.

6Larikova, I., J. Fleckenstein, A. Chokhachian, T. Auer, W. Weisser, and K. Dörfler. 2022. Additively manufactured urban multispecies façades for building renovation. Journal of Facade Design and Engineering 10:105-126.

7Sweet, F. S., A. Mimet, M. N. U. Shumon, L. P. Schirra, J. Schäffler, S. C. Haubitz, P. Noack, T. E. Hauck, and W. W. Weisser. 2024. There is a place for every animal, but not in my back yard: a survey on attitudes towards urban animals and where people want them to live. Journal of Urban Ecology 10:juae006.

8Sweet, F. S., and W. W. Weisser. 2025. Welcome for thee, but not for me: How demographic parameters and nature experience affect how close to home people accept animals. Basic and Applied Ecology.